Beware: what follows is quite long. I take this to heart because this is possibly my favourite painting of all time…

On Wednesday, 26th of February 2025, the Guardian ran with this headline: “Fresh doubt cast on authenticity of Rubens painting in National Gallery”.

The ‘fresh’ word is notable: this re-heated argument was first cooked up in the 1990s when a very expensive, potentially very important painting was acquired by London’s National Gallery. The painting is Samson and Delilah, and is a large panel painting depicting Delilah cutting Samson’s superpower locks.

The allegation is that the Rubens painting in question is not actually by Rubens, not even of 17th century date, and in fact a 20th century copy.

Who’s saying this? Over the years, a few people have been involved in the Rubens-truther movement. Some have added their names, and then dropped out (Waldemar Januszczak). One person in particular, though, has stuck to the argument, and she is the source of the headline: Euphrosyne Doxiadis.

In principle, I’m sympathetic to anyone trying to test orthodoxy. For all its ambitions for transparency and enquiry, academia can sometimes close ranks around certain sacred ideas. I’ve written before about the pitfalls of peer review when dealing with new skepticism, through the lens of Saul Newman’s work on blue zones.

The way academia finds out if research is ‘legitimate’ is to ask an anonymous panel of people with inevitable vested interests and biases. If you’re attacking their field, you can be sure you’re likely to be gatekept out. This is presumably why Euphrosyne Doxiadis’ claims have never appeared in a peer-reviewed journal, and why her account has waited decades to finally enter print through a coffee-table type publisher (though it seems to be owned by Columbia University Press). Doxiadis is an art historian, but her background is in Fayum mummy portraits greatly predating Rubens, and made with completely different techniques. Still, I don’t think this should be a reason to ignore Doxiadis’ claims in principle.

I don’t think that any of the above is a substantial critique of Doxiadis’ arguments—though I strongly suspect all of the above will appear in the counterarguments of her work. Note that, at the time of writing, I haven’t seen a fresh wave of criticism from others, yet. The National Gallery has declined to comment so far. I suspect they’re avoiding wading into controversy and want it to blow over.

I have some sympathy for Doxiadis, the plaintiff. I do not have much sympathy for her case. We have to deal with her arguments on their merits, and the problem with the arguments is that they don’t have much merit.

Here are Doxiadis’ main reasons for saying the painting is fake:

The painting is on a panel that’s only 3mm thick and glued down to blockboard, which is inherently suspicious and, further, the painting was really made on a canvas and then glued down to an old panel and then glued down to a blockboard.

The style and paint handling is wrong.

Samson’s foot is cropped out, which Rubens wouldn’t have done, an old engraving shows a full foot, and also is a hidden sign that the painting was a copy.

An AI program says it’s fake.

A claim of fakery requires a counter-argument, and Doxiadis’ counter claim is:

The painting was created by a trainee art conservator from Brazil called Gaston Lévy while he owned the painting before 1929 (according to a document I haven’t seen a reproduction of, hopefully it’s in Doxiadis’ book).

The argument that it’s specifically Gaston Lévy isn’t as important in my view as the foundational points 1-4, which are necessary for considering point 5 at all. I’m going to deal with all four points in sequence, because I think this is important and rather interesting stuff.

Argument 1: the fishy panel

Modern blockboard, behind a Rubens painting from 1609-1610? Certainly sounds suspicious, doesn’t it!

Most paintings of great age however have been abused, battered and transformed over the years, and this is especially the case for their supports.

Canvas paintings are typically ‘re-lined’, meaning they are cut out of their original stretchers and glued under heat and pressure to a stronger backing canvas. This is a routine operation; very, very few paintings in the National Gallery haven’t had this invasive surgery done to them. The National Gallery states this openly, by the way, in their publications.

Panel paintings are almost always planed down to a greater or lesser extent. The problem with wood is that it is moisture sensitive, and the many planks that make up panel paintings tend to ‘cup’ which ruins the experience of looking at a painting (imagine the reflections) and causes paint to ping off like a lost spring.

Here’s a late 19th century description of the kind of thing that happened to wooden panel paintings to correct all this distortion:

But all had to be planed down at the back, and those which had warped subjected to heavy pressure so as to bring them back to a level. […] When all were once more in place, and firmly united, the whole was stoutly parqueted at the back, and the picture itself now presented a perfectly even surface. [Quoted in Martyn Wyld, The Restoration of Holbein’s Ambassadors]

The panel described above, one of the most famous paintings in the world, is The Ambassadors. How much did the Victorians plane that venerable oak surface to? 5mm.

Doxiadis tries to cast doubt on the idea of the Rubens panel being planed to 3mm, suggesting it such a process wouldn’t be physically possible. This is far from the truth. Panels were routinely planed to sub 1cm thicknesses in the course of the 19th century. A survey of Renaissance paintings points this out. NG4444, The Virgin and Child with Four Saints and Twelve Devotees: planed down to 5mm. NG3899, Saint Paul: original panel 7mm thick. NG1665, Portrait of a Man aged 20: planed down to 5mm. Should I go on?

Yes, the treatment of the Rubens painting seems a bit harsh given its date, but physically impossible or suspicious it is not.

What about the blockboard? Doxiadis seems anxious about when exactly the blockboard was glued to the back of the thinned panel, but it’s really not very significant. Again, superficially such a material seems ‘strange’ or ‘cheap’ or just fishy, but once you look into conservation practice it makes a lot of sense.

The last thing you want to use to stabilise an uneven, organic material that is reacting to differences in humidity and temperature is glue it to another organic material with its own knots, humidity levels, and an uneven thickness. That is, you absolutely wouldn’t glue down a thinned panel onto a natural support.

In 1984, a huge renaissance painting by Cima de Conegliano had to be ‘transferred’ from its original panel onto a new support. First the painting was planed down from 5cm to 1cm thickness. Then it was glued down onto an aluminium honeycomb panel with fibreglass mesh supports. Doesn’t sound very Renaissance, does it? But such a panel is reliable. Blockboard, similar to plywood, might not be as sophisticated as aluminium honeycomb but because of the small strips of wood it would be much less prone to movement.

The ‘smoking gun’ of the panel doesn’t seem very smoky once you take a closer look at conservation practices and their history. But Doxiadis’ counter-theory is far less plausible than any of this. She claims that the painting was actually made on a canvas and then transferred to panel and then subsequently glued down to blockboard. She claims this in spite of the fact that no canvas, whether in trace or in bulk, was discovered in the 1980s assessment and treatment of the painting by Joyce Plesters.

None of this matters, really, because if the painter of this work—whoever it was—painted it originally on canvas you could tell with the naked eye. Canvas is a woven material with depressions and peaks. Thick paint skips the troughs of the weave; thin paint get stuck in the depressions. Canvas paintings look like they were painted on canvas, and you would be able to tell this with Samson and Delilah.

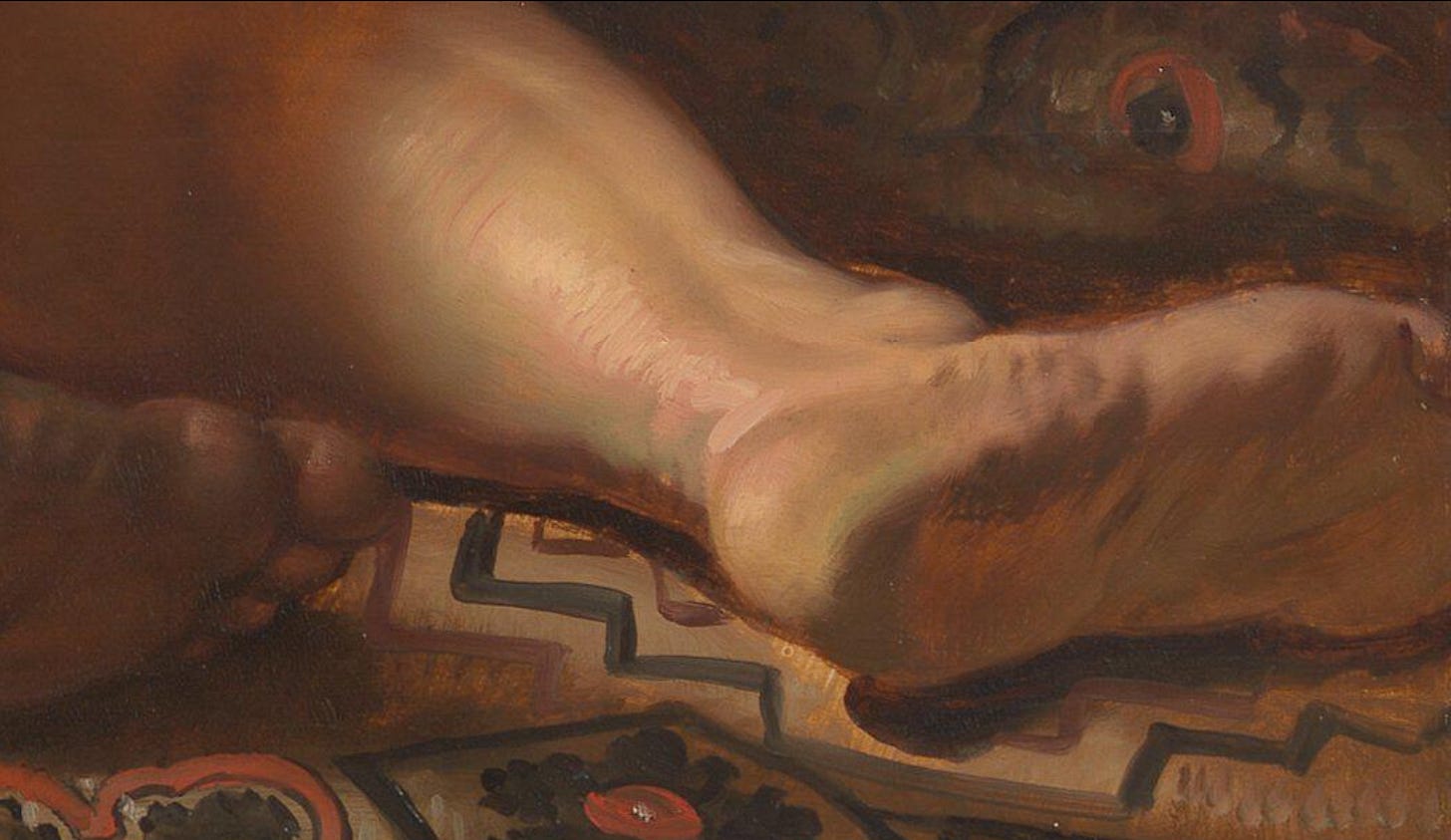

There are no such textural effects in the painting. Instead, there is the characteristic ‘stripey’ effect that Rubens always achieved in his paintings on wood. He liked to use a stiff bristle brush and paint the imprimatura with even diagonal strokes, DIY style. That’s what’s going on with Samson and Delilah, and you don’t need a microscope to see it. Indeed the painter of this work was so happy with that particular finish that they left it visible through Delilah’s sleeve.

To conclude this whole panel business, the arguments about the panel fall down as soon as you look into the history of conservation and the technical details of many paintings of great age. The idea that the painting was originally made on canvas is absurd.

Argument 2: The style’s wrong

My patience wears a little thin with the photographs showing “shoddy” workmanship used in the Guardian article and presumably Doxiadis’ book. Why are they in black and white? The black and white photographs have the effect of making the painting look unfamiliar, and cunningly make it look far worse than it really is. Without the modulations of colour, each brushstroke looks coarse and thoughtless. This is bad faith, dare I say it, manipulating evidence.

You can see that the black and white reproductions work against the right hand image (from Samson and Delilah).

Sure, there is a difference in style between the two paintings selected by Doxiadis. But Rubens modulated his style all the time. When working on panel paintings, his works look completely different to canvas, and when working at different scales he would play with looser brushwork (particularly in his sketches, which are almost always on small wooden panels).

Loose, playful brushwork as that in Samson and Delilah is a classic sprezzatura approach. This is ‘artful artlessness’, or ‘careful carelessness’ whereby a painting simultaneously looks real and made of paint. This idea was introduced in the 16th century in the Mannerist movement, which early Rubens was a part of. Samson and Delilah was painted at the very beginning of his mature phase as he was starting to move away from the more intense aspects of that style. The playful and even witty hallmarks of mannerism are still very much on display here.

Contra Doxiadis, the paintwork in Samson and Delilah is some of the greatest in the history of western art. The brushwork is bold, daring, and the use of pigments shows an intimate understanding of colour that few copyists would dream of. The curtain of rich purple is actually a mixture of translucent red (kermes lake) and carbon black—no blue! The flesh tones are a complex interplay of the imprimatura (coloured ground) and thin layers of whites and oranges above it. The ground even comes through Delilah’s red velvet drapery, creating a shimmering orangey mid-tone. Not to put too fine a point on it, this paintwork is the envy of the world. I wish I could paint this well.

Furthermore, the ‘copyist’ hasn’t put a foot wrong in their pigments. All are correct for the period: red lakes based on insect and plant bark, vermillion red, carbon black, lead-tin yellow, lead white, natural earth brown, azurite and malachite for blue and green. Dozens of new pigments were discovered in the 19th century, and the ‘copyist’ has managed not to use any of them. Yes, this is possible, but less likely, especially in view of all the other evidence.

Argument 3: Samson’s foot chop

Samson’s foot is cropped off in the London Samson and Delilah. It is unusual for important features of paintings to be cropped off deliberately in pre-modern art. The cropping craze gets going with the arrival of Japanese prints in the 19th century.

Not all cropping is deliberate, however. See above: panel paintings get cut up, trimmed down, sometimes severed into many different pieces like Duccio’s Maesta which is now dispersed in collections across the globe. Cropping of something only slightly important like Samson’s outstretched foot could easily occur in the cutting down of the painting, due to damage, not fitting into a desired frame, random caprice, etc.

Doxiadis takes the cropping as a secret signal that the painting is indeed a modern copy, a cry for help saying “no I’m not really real!”. The irony is that Rubens’ original ink sketch also crops out the foot! So does Rubens’ preparatory oil paint sketch in Cincinatti! In fact, the only evidence for an un-cropped foot in the composition is an engraving by a different artist and a painting within a painting by Frans Franken.

It’s possible both artists ‘corrected’ Rubens by adding a foot; it’s possible a foot was added on to the painting, and it’s also possible that it was cut off after those two early copies were made. In any case, it’s prima facie irrelevant to authorship. It’s also particularly unconvincing given the ‘whole foot’ story isn’t matched by the other autography Rubens compositions that survive.

Argument 4: Computer says no

The latest wrinkle in the story, the idea that an AI program tells us that the painting is fake. This has been presented as a really compelling argument in its own right, and the way it has been framed is that the technology “backs” the argument, and the fact it is so cutting edge means it is all the more compelling.

How about taking things the other way: shouldn’t the cutting edge nature of the technology cast doubt on its conclusions? Why does ‘newness’ or the glitz of great computing power defend a conclusion from scrutiny?

As those I know that are familiar with using artificial intelligence to a fairly deep level point out, “junk goes in, junk goes out.” Everything you put into an algorithmic model matters, and the way you train it and potentially bias it can mean your answers are worthless.

In a rather breathless press release, the trainer of the algorithm in question stated:

We repeated the experiments to be really sure that we were not making a mistake and the result was always the same. Every patch, every single square, came out as fake, with more than 90% probability.

It is bizarre to me that a scientist with a quantitative background (Carina Popovici), would say this. If you chop up the same sample—the Rubens painting—into loads of little squares, you’re not increasing the sample size. What’s worse is this is apparently the same thinking behind their ‘massive’ data set for training the model of 2392 “data points”—actually 148 paintings in little byte-sized pieces.

The argument would bear a little more weight if it replicated the ‘test’ on other paintings that we know the authenticity of, and showed us the actual images on which the model was trained. The ‘report’, which is really a brief press release of five pages, does not tell us what the training set was nor the criteria for selection. Popovici said a few years ago that the academic article with the full dataset and methodology was yet to be released; I can’t find it on Google scholar.

The use of four significant figures: ‘91.78% likely to be a fake’ is rhetoric through numbers. This is a probability spat out by a computer with no account of the uncertainties involved. Giving four figures in this context is tendentious and, frankly, silly.

All the ‘AI analysis’ demonstrates here is that if you train one programme with a limited number of images and no clear methodology it ‘thinks’ that the painting isn’t real. How is this better—or substantially different—than a gut feeling from one member of the species homo sapiens?

Wrapping things up

If you are going to tackle empirical evidence, like that which exists for Samson and Delilah’s date and authorship, you need a really solid grasp of its details. The critiques, though, read more like misunderstandings of those details combined with some unlikely conjectures—conjectures much harder to believe than the simple idea that it is just a Rubens painting.

There is so much to doubt in history. Yet there is a habit of doubting things which are actually very well-founded, even if the case may be imperfect. The reason is probably because the well-founded stuff is such a high value target, likely to garner a great deal of attention and which can create a compelling journey for those that go down the rabbit hole.

I think, dear reader, that this Samson and Delilah painting is 100.0000% likely to be a genuine Rubens. This Rubens is an authentic Rubens as the day is long. This authentic Rubens is indeed not only a genuine Rubens, but it is a lodestone of Rubensian perfection such that many other works, even autograph works, pale in comparison to this one painting. Perhaps that’s why it’s so controversial?

One of the mathematical facts about 100% certainty is that it means that no _possible_ evidence, no matter how overwhelming, could ever make you less than 100% certain again. Even if the original painting turned up down the back of someone's sofa, along with the notebook kept by Gaston Lévy during the period that goes into great detail about how he copied it, you'd have to stick to 100% certainty at risk of mathematical incoherence. P(x) = 1 -> ∀y∈F P(x | y) = 1.

I take it that you didn't actually mean to make a strict mathematical claim, but were just ironically rebutting the fake maths of the AI 'analysis'. But I think it's interesting to ask under what circumstances you might actually reasonably come to be 100% certain, in the strict mathematical sense, in an attribution of authorship.

The example I think about the most is the Pauline epistles. It is relatively well-known that most scholars agree the 'Pastoral' letters to Timothy and Titus were not written by St Paul. This is usually explained by pointing out that the writing style in the Pastorals is very obviously different from how Paul wrote, and the theology in those letters is also significantly different from Paul's own theology (so significantly different that it's almost impossible to have been the result of a simple change of mind). But some people have a follow-up question: how do we know what Paul's writing style and theology were _really_ like? The answer is 'based on the authentic letters', but now the answer is circular: we know which letters are authentic based on writing style and theology, but we know about Paul's writing style and theology from the authentic letters. Why can't we say that the Pastorals are authentic, and the ones that differ from them must be spurious?

There are some more substantial answers to this question, but I think the most fun way to respond is: the guy we are interested in is the guy who wrote the masterpiece we call 'The Letter to the Romans', _whoever that was_. If it turns out that his name actually was Paul and he really was a first-century Christian missionary, great. If it turns out that his name wasn't actually Paul and he was a Greek pagan trying to write a parody of these Jewish apocalyptic preachers, we could still call the guy 'Paul' for ease of reference, and we'd still be just as interested in what 'Paul' wrote. And if it turned out it was a pious forgery by some second- or third-century Christian, we'd just lose interest in the historical figure, and keep writing about the author, at most maybe adding a 'Pseudo-' to the start of his name. (This is exactly what happened with Dionysius the Areopagite: nobody cares about the historical figure any more since it turned out that he didn't write the works attributed to him.)

In a certain sense, then, we can be 100% certain that Paul wrote the letter to the Romans, and no evidence will ever make us less certain; because, in a certain sense, what we mean by the name 'Paul' is 'the guy who wrote this text', so it is true by definition. The current state of scholarship is that we can be pretty sure that this guy was actually a real historical figure named Paul, who lived in the period he claimed and had the life experiences he wrote about. But even the most radical new bit of evidence wouldn't cause us to file the text away forever as a forgery, and start trying to reconstruct the life anew; at most we would instead file the life away forever, as irrelevant for understanding the text.

I don't think you'd necessarily go this far, but there are echoes of this idea when you write:

> This authentic Rubens is indeed not only a genuine Rubens, but it is a lodestone of Rubensian perfection such that many other works, even autograph works, pale in comparison to this one painting.

The difference with Rubens is that there are a lot of works one might be interested in with him, and many are unambiguously and uncontroversially associated with the life of a historical seventeenth-century figure, so we cannot so easily redefine the name 'Rubens' to mean 'the guy who painted this Samson and Delilah'. But I wonder if you're gesturing at the idea that Rubens only deserves so much attention to the degree that he actually painted this work; if he did not paint this work, our understanding of what Rubens stands for in art history would have to be radically changed. You're not going all the way towards re-definition, and thus not all the way towards certainty; but it's a lot closer than others might realise.

You’re very convincing !