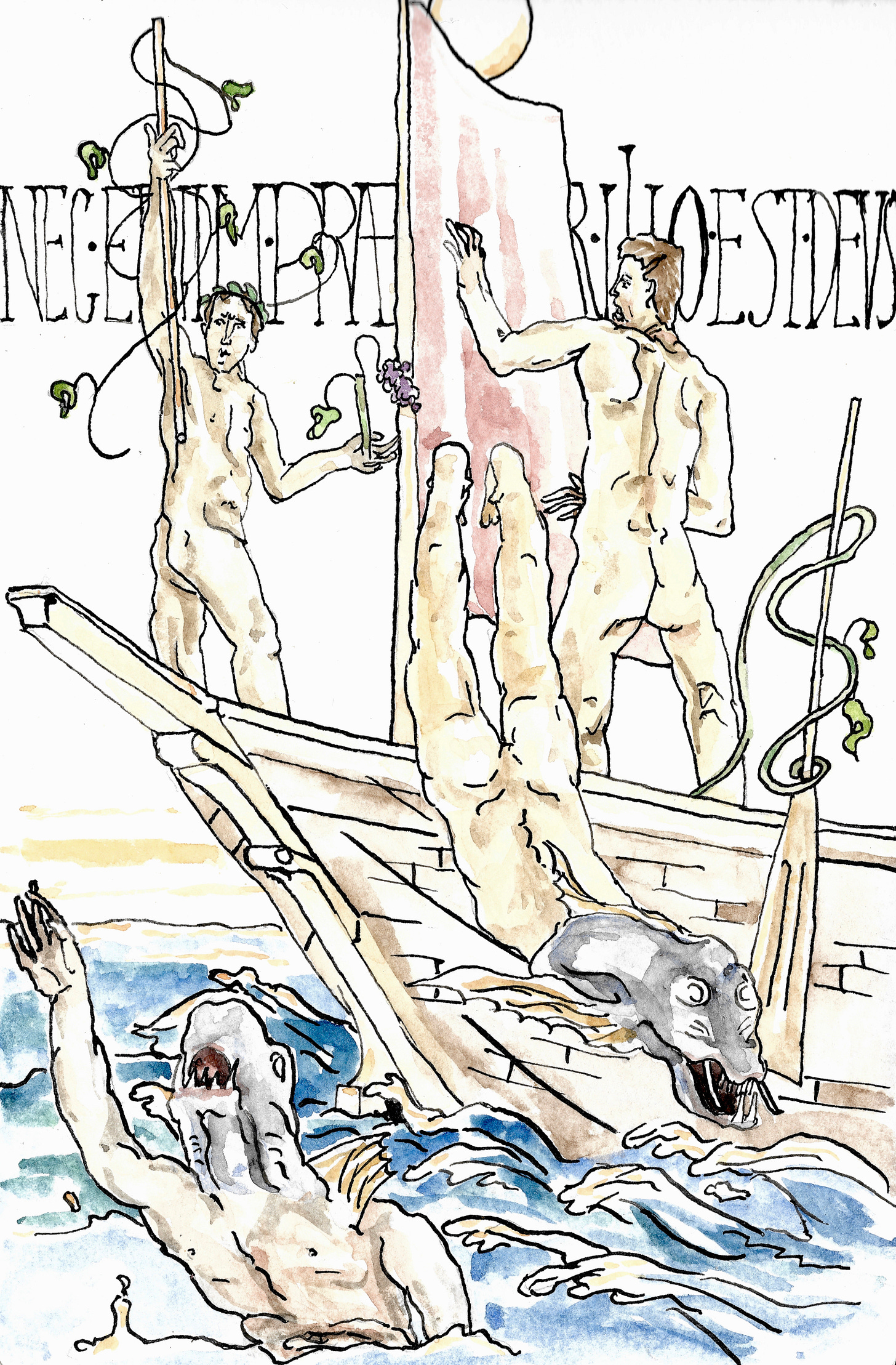

When Bacchus revealed his divine form to the sailors that tried to abduct him, the narrator of the story declares nec enim praesentior illo est Deus: “Be assured it was the God!” It is a dramatic moment in the ancient Roman canon of belief. One of the most important gods appears to mortals in a scene far more bizarre and captivating than the Christian story of crucifixion. Strange as it may seem, the Romans believed in their own religion. They believed sincerely in their many gods, and their many strange and often horrifying interactions with people. They did not believe they were making it up.

Bacchus reveals his divinity to the sailors, who promptly jump into the sea and turn into dolphins. Pen and ink on paper (By the author, 2023)

Every time I search for a new subject to draw or paint in my evenings or weekends, I look into what’s called ancient Roman and Greek mythology. The great paintings of Titian covering the transformation of people into beasts, stars, and other natural phenomena, are known as his mythologies.

The ancients would be turning in their sarcophagi.

What do we mean when we say “mythology”? The problem with the word is that it doesn’t really mean very much. “Mythology” only comes into play once a belief system has been battered, extinct, or is otherwise not taken seriously by some unknown consensus of society. Thus, non-muslims do not talk of ‘Islamic mythology’, just as muslims do not talk of ‘Islamic mythology’.

We might, conversely, talk ironically of ‘football mythology’, or ‘urban myths’, but never ‘football scripture’ or ‘according to the tenets of urban religion’. We can see in this way that ‘mythological’ is a marker of something approaching religiosity, but which is nevertheless considered illegitimate by common consent.

So, when Emperor Constantine changed world history forever by turning Christianity into an Imperial religion, did he turn all that 'Pagan stuff’ into mythology forever? Perhaps. I suspect it didn’t happen quite as quickly, but given a few centuries of Christian dominance in most (but not all) of Europe, the Pagan histories that were once considered quite seriously became a whimsical literary canon and eventually fodder for artworks. Christian authors writing about ancient Roman religious practices assumed that the collective nature of Roman worship and its connection to the Imperial state made it all cynical, its adherents little more than part-timers, mediterranean morris dancers.

Perhaps most telling about our concept of ‘mythology’ is the Renaissance application of ancient Greek and Roman imagery. The narratives became an excuse for erotica, a Trojan horse if you will, for the depiction of naked bodies and scandal. This demonstrates the contempt in which the ancient stories were held. At one level, the stories might be deployed to show your learning and literacy. At another, they could never be considered real history, and form (titilation) became function.

Venus and Cupid, silverpoint on prepared paper (By the author, 2023)

Yet modern neo-Pagans seem to use the term ‘mythology’, which I think is a mistake. ‘Mythology’ is an exonym, a term used about an out-group, about something that is inherently incomprehensible. What they are talking about, as adherents or at least sympathetic ears to these pre-Christian beliefs, is religion.

The opposite of this whole process is the atheist’s talking point that the shelf of ‘mythology’ is just the shelf of religions that no one believes any more. This is, unavoidably, true—there’s no other meaning in the word ‘mythology’. However, I think it is also a matter of historical accuracy, and perhaps respect, to refer to the tales of these mostly ignored religions as what they were: religion. For this reason, I like to refer to the tales illustrated above as ‘stories of Roman religion’, or similar, even if it’s wordy. And I think you should too.

Ceres arrives with her ‘sacred dragons’ and turns Lyncus into a lynx, who has been busy trying to murder Triptolemus in his sleep. Triptolemus has just taught Lyncus him the art of agriculture, but refused to teach it to Lyncus’ people. (By the author, 2024).