One of my most deeply held beliefs is that unexceptional art is worthy of study. I don’t mean this in the sense that it’s normally meant. I do not mean that we should study vernacular art, or ephemeral art: media which are overlooked. Of course we should do that. What I mean is that we should study art whose quality is unexceptional. Works of art which are good, very good, but not excellent, are deeply instructive. Good art does not just show really great art in higher relief; rather, the good ordinary helps us better understand the mechanics of what makes art good and bad in the first place.

When I think of the ‘good ordinary’ in cultural history, I tend to think of the old brown paintings produced in England after the death of Sir Anthony van Dyck. There are wonderful paintings produced in that period, but they are stunningly conservative. The formats that Van Dyck introduced, the offhand classicism, the extensive drapery, the figures pointing demonstratively at nothing particular, remained hegemonic right up to the end of Sir Joshua Reynolds’ overblown career. That makes a stretch of over a century and a half. It’s not that all art has to be ultra-new, but these painters just didn’t do enough innovation to make pantheon. I love Sir Peter Lely as much as the next chap, but he just isn’t as important as Titian.

Nevertheless, much can be learned about painting well—and with sophistication—from Lely. In some cases, Lely is probably more instructive than a giant like Titian, because we tend to get dizzy looking up at such colossi. Practically, the reams of literature produced about the very top of the canon is completely overwhelming. It makes further research more difficult, not less, for the simple fact that you have to read everything that’s been written about the subject before you can get started.

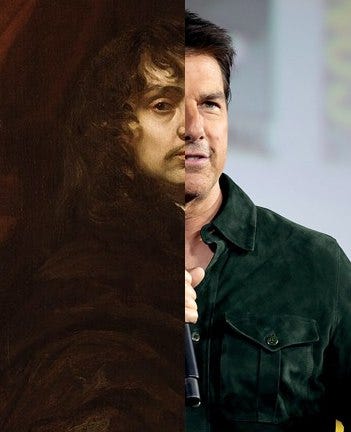

Tom Cruise is hardly the Peter Lely of his generation. Cruise is a household name. Lely is a name you drop in a room full of art historians so that you can look edgy in a kind of tweedy-reactionary way. Tom Cruise is massive, but the kind of film he tends to accompany has an important similarity with what I’m getting at about Lely. The films that Cruise acts in are genre pieces: they are not fundamentally innovative, they are not avant garde, they are not arty or challenging. They’re very good examples of the genre they inhabit, which is action. This is what film critics like Kermode mean when they say (as they often do): “it does what it needs to do and it does it well.”

Art doesn’t ever need to do anything. By definition, it’s non-functional. But the mechanics of genre are so rigid that they’re pseudo-functional. An action movie must deliver thrills at a given pace just as a threshing machine must separate grain from husk at a given pace. Neither action flick nor threshing machine is ever transcendental: they achieve what they must within particular parameters and they shouldn’t break those parameters. But both can be outstandingly effective at what they must do.

The films of Tom Cruise, to my mind (excepting Magnolia), tend to have a particularly potent sense of genre-service, an absolute commitment to, and respect for, its tropes. Tom Cruise embodies the action movie down to the level of his body: he does his own stunts. Increasingly, the stunts are unhinged in expense, scale, and actual danger. At the same time, Tom Cruise’s personal beliefs mean that his films have to stick to strictly a-political lines. The recent film Top Gun: Maverick for example has an eery sense of stepping around the fact that the villains are probably Russia or, rather, a ghost thereof. It’s set in a chilly boreal landscape but there are no identifiable markers on the enemy jets, and no-one is ever named in the ‘mission brief’.

Tom Cruise does not want to be a ‘suppressive person’. This is terminology of the cult of Scientology, and it means that Cruise doesn’t want to be bad, negative, bringing people down, and so on. The films he takes part in and the characters he plays are never ‘suppressive’: the outcomes are always unambiguously positive, the enemies safely abstracted so they can be blown up without an ounce of viewer guilt.

Unreliable sources claim that Tom Cruise is possibly giving up his connection to the Scientology cult. This is a good thing for Cruise, a good thing for his wallet, and potentially a very good thing for the world if he then diverts his massive earnings to a real charity. However, there will be a slightly disappointing edge as Tom Cruise gets his ability to play a full range of characters back, and his producing-role choices are less constrained. There is something utterly fascinating to me about the idea that Cruise’s artistic choices are constrained by the mores of a 20th century science fiction cult. Oh well.

Bringing things back to Sir Peter Lely, the observation I want to make here is that very good, even excellent art is often produced with extremely constrained vocabulary, with very limited options. That art might not necessarily be the greatest the world has seen, especially if that vocabulary has been inherited from others (i.e. Lely and his contemporaries and followers’ intense reliance on Van Dyck). However, constrained art is deeply important. It’s a modest but meaningful contribution to the world which can often be more enjoyable than the shrill moments of avant gardeism. Moreover, watching, understanding, and looking at art which is good but not transcendentally ‘new’ encourages us to think about artists and their relationship with limitations, about genre, and what makes images—moving or static—pleasing.

Andrew Key (@rolandbarfs) wrote a good piece on Cruise: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/tom-cruises-late-style/